Almost 110 years ago, on July 7, 1913, Edith Rigby, a suffragette from Preston, burned down Lord Leverhulme’s bungalow in Rivington.

On her arrest she posed the following question “I would like to ask Sir William Lever whether he thinks his property on Rivington Pike is more valuable as one of his superfluous homes occasionally opened to people or as a beacon lighted for King and Country to see that here are some intolerable grievances for women”. Over a century later, opinion is still divided on this outrageous act. What do we think now? Chairman of the Horwich Heritage Stuart Whittle explores....

The fight for Votes for Women

In order to understand Edith’s actions, we have to understand what she was fighting for. Women in Britain had been trying to obtain the vote for many years and were getting nowhere.

So in 1903, Emeline Pankhurst and her daughters Christabel, Sylvia and Adela and a small group of women based in Manchester founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). The aim was to ‘wake up the nation’ to the cause of women’s suffrage through ‘Deeds Not Words’.

In 1906, the WSPU relocated their headquarters to London in order to be able to protest where the Government was situated. They maintained a constant presence in Whitehall, petitioning Downing Street, heckling MPs and chaining themselves to Government buildings. They also used art, debate, propaganda and attacks on property (including window smashing and arson) to draw attention to their cause.

Galvanised by the actions of the WSPU, the ‘Votes for Women’ movement spread rapidly across the country. In June 1908, suffragettes from all over Britain gathered in London on ‘Women’s Sunday’ to process through the capital, attracting a crowd of 300,000. This was followed in 1911 by a ‘Coronation Pageant’ (inspired by the Coronation of George V) which was four miles long, drew an even bigger crowd and culminated in a rally at the Royal Albert Hall attended by over 60,000 delegates.

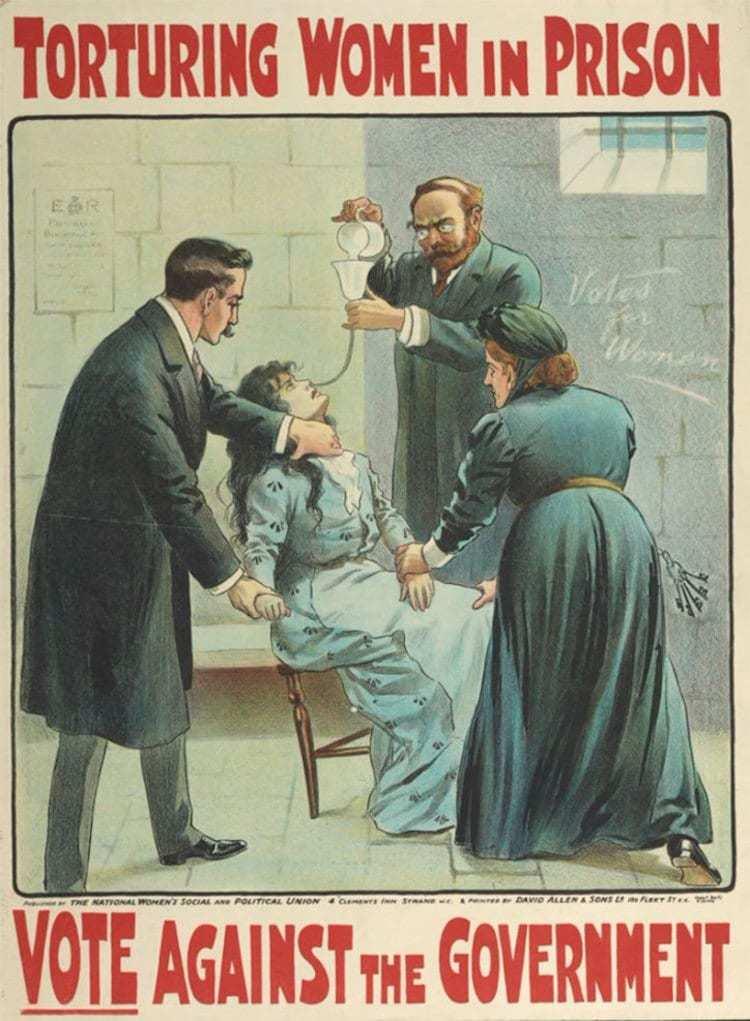

Tensions continued to rise in the face of Government inaction and acts of protest, vandalism and arson became widespread. As a result, over 1,000 suffragettes, including Emeline Pankhurst and her daughters were sent to prison. Many were sent to Holloway Prison in North London, where they protested against the refusal to treat them as ‘political prisoners’ by going on hunger strike.

In response, the Government introduced a policy of ‘force-feeding’ and, when this failed, a law was passed in 1913 (referred to by the suffragettes as the ‘Cat & Mouse’ Act) to allow hunger-striking women to be released from prison when they were ‘weakened’ on ‘licence’.

Once their health was restored, or they resumed their militant actions, the women were re-arrested and returned to prison – only for the process to be repeated all over again. Hence the term ‘cat and mouse’ for the ‘game’ that was being played between the police and suffragettes.

This wave of militant action and public protest only ceased at the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 when the suffragettes agreed to suspend their campaign and fully support the war effort.

Edith Rigby’s militant actions

Protests, vandalism and arson spread across the country as the ‘Votes For Women’ campaign gained momentum.

In the North West, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenny were arrested for disrupting a Liberal Party conference at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester and in April 1913, two days after Emeline Pankhurst was arrested after taking responsibility for damaging the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s house in Surrey, three suffragettes were arrested for damaging 13 valuable paintings in the Manchester Art Gallery.

Edith Rigby’s uncompromising approach to the cause of women’s suffrage led to increasingly militant action both in London - where she was involved in a number of clashes with the police outside the Houses of Parliament - and in Lancashire, where she committed what we would consider today to be ‘atrocities’.

She pelted an anti-suffrage MP with black puddings at Manchester Free Trade Hall, planted a bomb in the Liverpool Corn Exchange, poured acid on Fulwood Golf Course, defaced the statue of Lord Derby in Preston, committed arson at Blackburn Rovers Football Ground and burned down Lord Leverhulme’s bungalow at Rivington on July 7, 1913.

It is for this act that she is still remembered as a controversial figure in our local history.

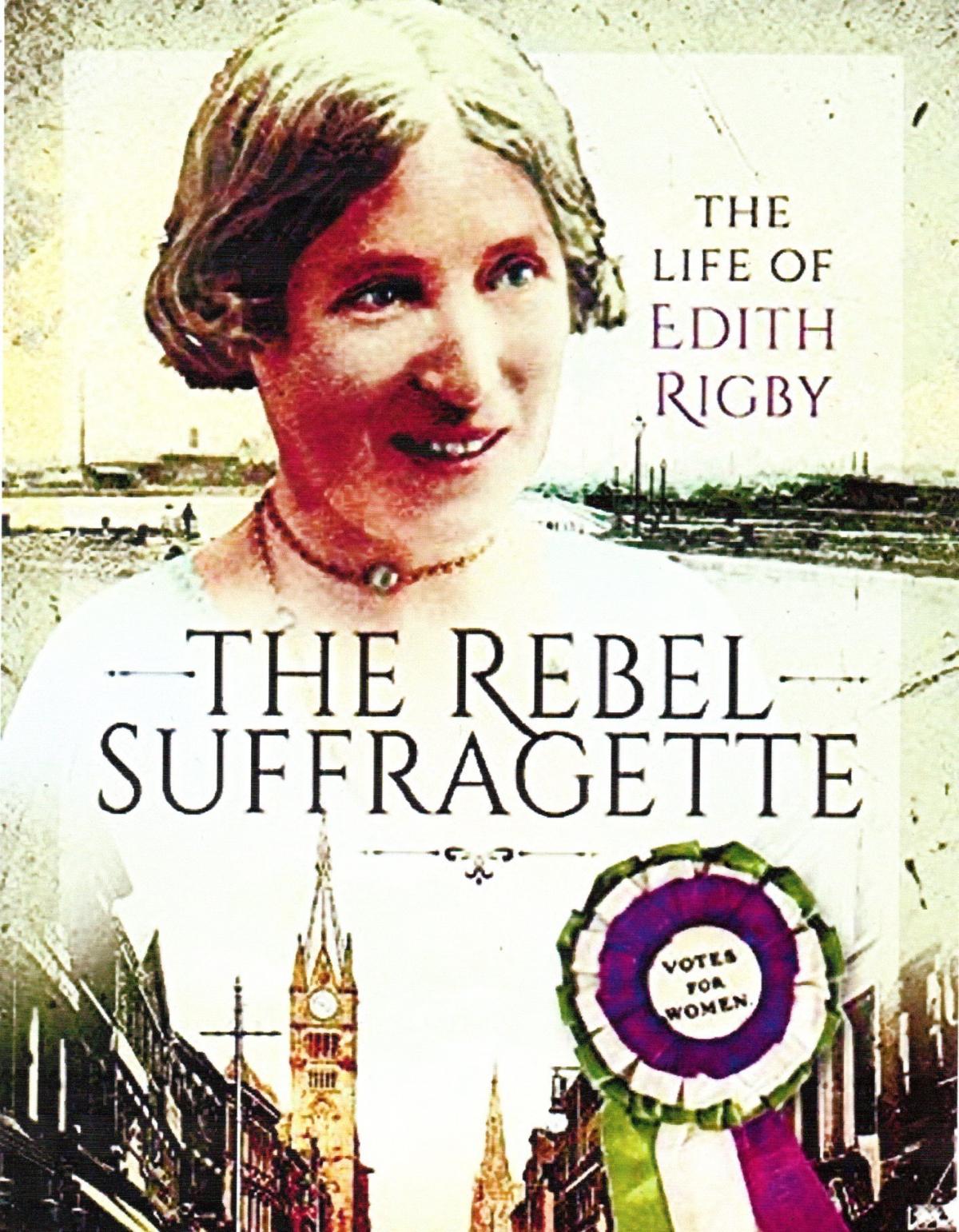

Edith Rigby’s life

Edith was a progressive woman who, from an early age, spoke up for the working class people of her home town.

Much to the embarrassment of her family, she fought against unfair divorce laws, founded an after-work club and night school for mill girls and started the local suffrage movement. She was also the first lady in Preston to ride a bike complete with ‘shocking’ bloomers which resulted in her being ridiculed and pelted with rotten fruit and vegetables.

At the age of age of 27, she married Dr Charles Rigby and moved to Winckley Square, a wealthy area of the town, but this didn’t stop her being a pioneer of Women’s Suffrage in Preston.

This resulted in much local criticism and abuse, and it was through the Suffrage Movement that she developed a close friendship with the Pankhurst family.

In 1907 she was arrested and imprisoned for taking part in a peaceful suffrage procession in Hyde Park, the first of several spells in prison where she was subjected to the horrors of the ‘Cat and Mouse’ Act.

In fairness to her husband, he did his best to support Edith and regularly petitioned newspapers, MPs and Parliament about the inhumane treatment meted out to the suffragettes.

Her own family, however, did not feel at all sympathetic and publicly condemned her actions.

Despite the hostility of many sections of society to the very idea of equal rights for women, Edith did make progress and particularly in her home town. In 1907, with the support of the Mayor, she founded the Preston branch of the Federation of Women Workers to fight for women’s rights and achieved significant improvements in local pay and conditions.

Why did she burn down the bungalow?

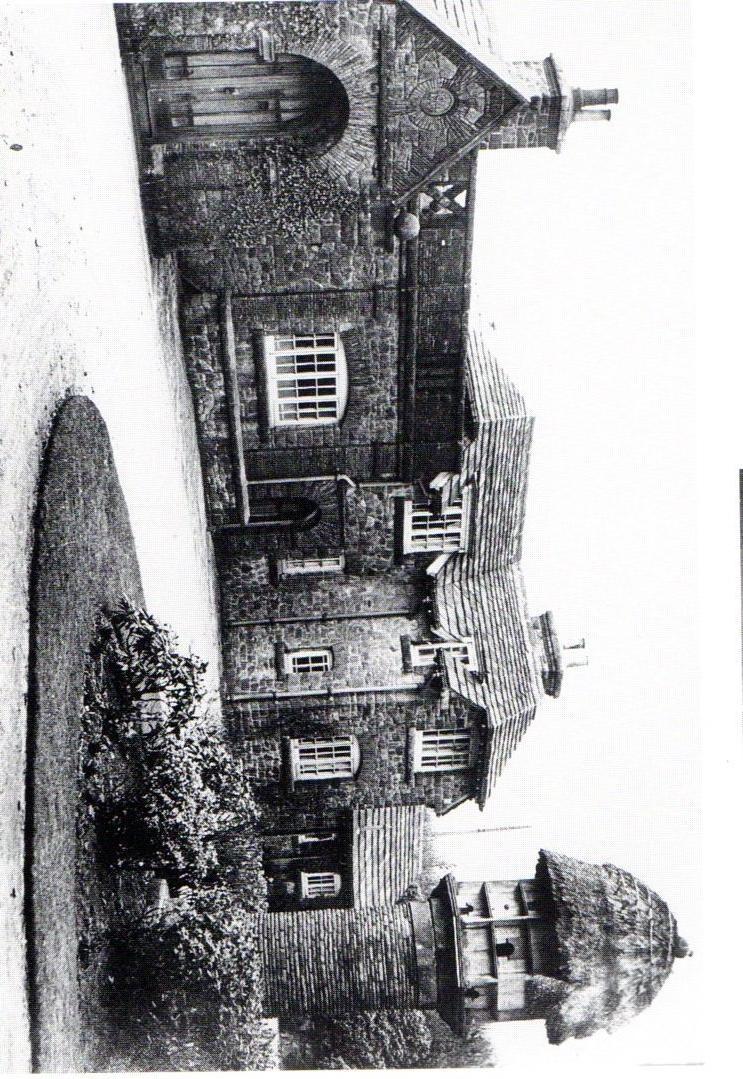

Lord Leverhulme was a Liberal politician who did in fact support the cause of women’s suffrage. But in Edith’s eyes his exotic hill top retreat represented an overt expression of capitalism in a world where there was so much inequality and injustice.

She made no attempt to hide or disguise what she had done. She gave herself up and was imprisoned (again under the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’).

What happened to Edith Rigby and the Women’s Suffrage Movement?

By 1914 things were at an impass between the Government and the Women’s Movement. The militancy of the campaign with arson, vandalism, damage and disruption had divided the nation.

However, when war broke out in 1914, all suffragette activities came to an end and the women (patriotically) turned to any sort of work that would help the country.

The importance of this war work was to pave the way for a partial victory when women over 30 were granted the right to vote in 1918. However, it was to be another 10 years before women had the same voting rights as men.

Even then it was slow progress. No women were elected to Parliament in the subsequent General Election and only a few emerged in the following years of the 20s and 30s.

During the war, with Women’s Suffrage ‘on hold’, and lots of women out of work, the ever- resourceful, Edith set up a cooperative jam-making venture to take advantage of the proliferation of local fruit and help with the food shortage.

This worked extremely well; so much so that Edith determined to set aside her political ambitions and join the Women’s Land Army. In order to do this properly she needed her own ‘patch’ and she duly bought a cottage, orchard, gardens and five acres of land in Howick, near Preston to set up her rural adventure known as ‘Marigold Cottage’.

She became a disciple of Rudolph Steiner with her love of nature, animals and all things spiritual but still found time to help found the Hutton and Howick Women’s Institute in 1920.

Her husband retired to join her at ‘Marigold’ but, after his death in 1926, she moved to North Wales and began an adventurous later life travelling extensively by land and sea while still following her healthy lifestyle. She died near Llandudno in North Wales in 1948.

What do we think of Edith Rigby now?

Even now, it is easy to be outraged by some of the things she and the suffragettes did. But they would argue that a non-violent campaign over a number of years had achieved nothing.

Edith’s whole life from an early age can be seen as a kind of ‘crusade’ and Women’s Suffrage was only part of it.

In fact the suffrage movement played a comparatively small part in her life’s purpose of helping the poor and oppressed, as witnessed by her endeavours and achievements for workers’ rights in Preston.

It was a time in British history when many fundamental social and political issues remained to be resolved, whether it was issues of class, workers rights, pay, pensions or votes for women, and people like Edith rose to the challenge and forced the pace of change.

Maybe we will always need controversial figures to point the way forward.

So was she justified in burning down Lord Leverhulme’s bungalow? She did at least make sure there was no one there at the time so that no lives were lost.

The damage to the property and its contents was extensive, valued at over £50,000 at the time. However, Lord Leverhulme was rich enough to be able to re-build it and replace the lost collection of paintings and antiques – and it did prompt him to build an even better bungalow which was sadly lost by what you could argue was another form of ‘vandalism’ in 1946.

On Saturday (May 13) at 10am, the Mayor of Horwich, Cllr Steven Chadwick, will open the Burning Down the Bungalow exhibition at the Horwich Heritage Centre, Longworth Road, Horwich. It will run until July 27. The centre is open every weekday 2-4pm and Saturday mornings 10am to 12.30pm.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel